Manners Stone Stories

And now – some Literature

Or at least something close. These stories were written here, beside a stone that appears unremarkable – unless you know where to look. It stands near the edge of Old Galtrigill, low and weathered, resting near smaller ones. It is so miraculous that it has a name, a place on the map, and more stories than it asked for.

Some say the stone improves manners, others claim it brings luck, though only under certain, mysterious conditions. There are whispers of fertility rites, bare skin against cool stone, and harvests blessed by ancient rituals. The stone itself, as always, remains silent.

One story tells of a minister who, denouncing it as a pagan idol, had it thrown into a ravine. The stone broke, but in time its fragments were gathered, carefully reassembled, and left to stand where it belonged. Whether this tale is true only the fairies would know — and they are not telling. The village that once surrounded it has long since vanished, yet the stone endures. People still bow as they pass, a few still sit upon it, though most no longer remember why.

What follows is a series of stories – written by the owner of the croft and keeper of the stone. No historical claims are made and no spiritual ones either. They are just a collection of tales that belong to this place, and to the one who stayed long enough to write them. You’re welcome to read them but you don’t have to believe a word.

How it all began: From Accident to Magic Infusion

No one remembers exactly when the fairies arrived on Skye—only that they never really left. They are not easy to date, or define, or catch. Most people know them from the names they left behind: Fairy Pools, Fairy Bridge, Fairy Glen. Which proves one thing, mostly they enjoy a good view, and they like to name things they didn’t build. They’re not particularly tidy nor particularly polite. But they’re curious, restless and very fond of echoes. Some stay briefly in mushrooms or potatoes, others in puns. Most are always on the move— between patches of light and edges of mist, between sounds and notions. And when the light is just right you might feel them pass. The best way to describe it is like a thought that didn’t start with you. They don’t live underground as much as between things: between rules, between seasons, between the last note of a song and the silence that follows. They like company and they like disappearing in the middle of conversations. The fairies of Skye are not all the same: Some are shy of light, grumpy, old as basalt. But the ones who came that night—they were the lively kind, the boisterous ones. Loud, laughing, as spontaneous as weather, a little disorganised, but warm-hearted. They were surely fairies with a taste for celebration. They hadn’t planned to meet at that particular spot as fairies rarely plan. They prefer to drift toward things—light, music, the promise of mischief. And that evening in particular, the promise was thick in the air. A Midsummer gathering which was no council, no conflict involved and no deeper meaning. The stone was a beautiful spot for celebrations which they had found by accident. Flat, generous, warmed from the day—perfect for sitting, dancing, tumbling over backwards in laughter. No one asked permission as they never do. Somebody had started humming, someone else had brought a jug, they leapt, they spun, they told stories that never finished. Someone played a flute with no holes and someone juggled sparks. And then —A sound. A subtle crack, like frozen earth giving way followed by a hush so wide you could walk across it. The stone had split, cleanly divided shockingly into three. They stopped and looked, followed by a chorus of "Oops" and then said what Fairies almost never say:“Ohsorry.” They tried to fix it, of course, out of embarrassment. It was so undignified, breaking a stone, especially such a graceful one. So they fussed, they pressed the pieces together with fern leaves, they hummed in harmony—well, almost. One of them blew across the gap and claimed the wind would remember how the pieces used to feel. They tried a drop of the evening’s last light, but nothing held. The stone remained split—three parts, oddly patient. And so, one of them knelt (which fairies almost never do) and placed a hand on the largest fragment. The hand shimmered slightly—not glowing, but becoming… clear. “Then take something better than wholeness,” they said.“ Take memory. Take attention. Take responsibility. We broke you by not noticing. So now—you will notice everything.” And they gave it what they rarely give anything: the power to feel and to change things for humans. To call someone closer when they don’t yet know why. To hold them in place until they see what matters. To send a thought that wasn’t theirs—yet fits. To reveal what’s hidden. To return what was lost. To make the forgotten moment loud enough to decide. To open a path. To close a wrong one. To shift a life by one quiet degree— until it finds its way. And from that moment on, it was no longer alone. Across oceans and centuries, it could sense the presence of other stones —touched, changed, waiting. It had become part of something larger: a quiet fellowship of listening places. Epilogue – What Remains The stone is still there split in three, rooted deep in the land where it belongs— and where its keeper watches and protects. Each year, when the days are longest and the air holds a shimmer, they return. Just for a while they remember what they did to it — and what they gave. It is an act of friendship, a way of saying: You are not forgotten. Fairies don’t keep calendars - they keep promises. Today many people pass by and some stop to sit without knowing why. They leave lighter, or heavier, or changed in ways they only notice months later. No sign marks the place, no legend explains what happened that night. But sometimes, if the light is low and the wind is just behind you, you might hear something shift. Not in the stone— but in you. It doesn’t speak but it is listening, and just might act.

The House, the Stone, and Two Unplanned Owners

About fifteen years ago they stayed in a house for a two weeks holiday that had once belonged to the singer Donovan. George Harrison, a Beatle, was a regular guest they were told. It was dark, damp, and faintly glamorous in a sad kind of way. The heating clanked like an old man clearing his throat, the toilet was an acoustic experience in its own right and there were spiders of prehistoric proportions in the corners. But the location—oh, the location on the shore of Loch Bay. From the top-floor bedroom window she could make out the far side of Loch Dunvegan. Most days the view was bright, and sometimes cloaked in soft mist or shifting weather, like the landscape kept changing its mind. But one thing never wavered: a white house tucked into the hill. Even when the rest disappeared, that house glowed brightly. She began to watch out for it—idle glances from the bed, usually in the morning until it became a quiet ritual. Would the house sparkle today? One day, they got in the car to explore the other side of the loch—a day trip: a bit of landscape, the Manners Stone, the usual curiosity about legends and where they might have walked. They stood by the Manners Stone, admiring the view across Loch Dunvegan toward the Waternish peninsula and agreed—something they rarely did—that this was the most beautiful landscape they had ever been to. Suddenly they saw the house. Very close to the stone stood a white cottage surrounded by a well-maintained garden—the last one at the end of the road in Galtrigill with a For Sale sign leaning like it didn’t mean to be noticed. It took a moment to understand, but when they looked back across the water they knew, yes, there, in the distance! That was the boathouse—their home for those two weeks. "This is it," she said somewhat excited looking at the cottage. "The glowing house. The only one in all of Galtrigill we could see from Stein. It must be really cheap—it looks so old and tiny, much smaller than it had from across the loch," she added. And a certain desire began to spread in her heart. They opened the gate carefully and knocked on the narrow door. A friendly gentleman in his seventies opened it and invited them in. “It’s all getting too much for me—the house, the garden, the two crofts that belong to this little estate. It’s time for a new chapter in my life. I want to move to Glasgow and live with my children and grandchildren. I hope to give my home into good hands.” Inside, the house was anything but small. The ceilings were quite low, but that had a certain charm. And as neither of them was two metres tall, it didn’t seem an issue. It provided everything they had never dared to imagine: tartan drapes, polished wood floors, a Rayburn in the kitchen, modern bathrooms, three bedrooms, an open fireplace. No palace—but a wonderful cottage, as if it had stepped out of a glossy interiors magazine, only warmer and without the smugness. Like someone had quietly built their wish list and left it waiting. Immediately in their minds, they were sipping sherry by the open fire, filling the Rayburn with the scent of stews and bread, perhaps building an orangery to cradle the view—two years later, they would. They imagined returning from the crofts, hands raw from planting trees, and sinking into the great bathtub, where the Outer Hebrides drifted across the window so close. The WOW factor, they decided, must have been invented for this very moment. From the instant they crossed the threshold, it felt inevitable. They hadn’t been house hunting, not even glanced at a listing. These were people who barely planned dinner, who let the days arrange themselves. But it was clear—without ceremony or surprise—that this house had decided choosing them, silent and certain. And so they said yes. Was it sensible? Not at all! But the view from the other side had been telling the future all along. The Manners Stone, of course, claimed credit. It always does. Said it had picked them itself to be the new owners (though the house might disagree). Sitting there like a retired matchmaker, quietly smug. And fair enough—since technically, the Manners Stone came with the crofts and the cottage.

Magnus MacAntler at the Manners Stone

I was checking the young rowan saplings when I saw him—a red deer stag standing beside the Manners Stone with the sort of bearing that left no doubt about who was in charge here. At least in his own mind. "So you're the tree planter," he said without even looking up. "Magnus MacAntler, in case you're wondering. Yes, I know—terribly dramatic. My mother had a weakness for Old Norse names and Scottish clichés." On Skye, one doesn't marvel at conversations with deer any more than at fairies that repair monuments—though even here, such exchanges follow certain rules. I checked my watch: 3:15 pm, third Thursday of the month. Of course. The Manners Stone had its own schedule for these encounters, a brief window when the ancient magic the fairies had woven into its fractured heart allowed understanding to flow between species. One precious hour each month when humans and animals share the same language, when thoughts translate perfectly across the species divide. I settled myself on a boulder, curious to see how this hour would unfold. "Pleased to meet you, Magnus. And yes, I plant trees." "Finally," he snorted, tossing his head back so his antlers gleamed in the light. "Do you know how long I've been waiting for someone here to show some sense? Centuries they've grazed everything bare—sheep, cattle, and my own relatives, the philistines. Not a clue about ecosystems." He tramped closer to one of the young trees and eyed the plastic tube I'd placed around the trunk. "What is this... thing?" "Protection. So you won't nibble it." Magnus looked at me as if I'd personally wronged him. "Nibble? ME? Please! First, I have refined taste. Second, I know perfectly well what reforestation means. And third..." He gave the tube a tentative lick and grimaced. "This tastes of chemicals and human ignorance. Revolting." "Sorry about that. But you know how it is with deer and young trees." "How it is with OTHER deer," he corrected me sternly. "Hamish, for example—the barbarian from Glendale. He eats everything green without a thought for tomorrow. Or that youth gang around Dougal in Borreraig—zero respect for ecology." He began pacing around the tree like a professor before his class. "You see, what you're doing here is pioneering work. Birches create windbreak and microclimate. Rowans bring back the thrushes, the thrushes bring seeds, the seeds bring diversity. In twenty years we'll have a small woodland ecosystem here." "You seem to know your stuff." Magnus stopped and stared at me as if that were the stupidest remark of the century. "I LIVE here. For twelve years. Do you think I just stand around looking handsome? I observe - I learn - I understand the connections between soil, water, plants, insects. Biodiversity isn't just a buzzword, it's survival strategy." He trotted over to the Manners Stone and leaned against it with the casualness of someone who belonged. "You know what the problem is? Humans always think in opposites: Either agriculture or wilderness, either useful or beautiful. But look at the Manners Stone—what are manners? Respect for what was here before you arrived." A gust of wind made the plastic tubes rustle, and Magnus wrinkled his nose in disgust. "Couldn't you at least use biodegradable material? That noise disturbs my afternoon nap." "I can try that." "Thank you. And another thing—if you want to plant more trees, take those spots over there by the old stone walls. More sheltered, and the soil's better because no one's trampled on it for generations." He stood up and stretched, then glanced at the stone with something approaching affection. "Remarkable thing, this old stone. Most days I can only grunt and snort at you humans, you know. But once a month, for one precious hour, we can actually talk. Share what we see, what we know. The fairies who broke this stone—they gave it many gifts, but this might be the most practical one." He turned to me with what I could only describe as a conspiratorial grin. "Right, I must be off. Still have an important meeting with the thrushes about berry bushes today. And then I need to have words with Hamish—the ignoramus trampled three more seedlings yesterday. Though I'll have to resort to antler-pointing and aggressive snorting for that conversation." Magnus turned to leave, but paused once more. "By the way—good that you're doing this. Many people talk about environmental protection, while putting up plastic domes for sweating chemicals into the soil . Why not try cultivating mushrooms? No petrochemical tents needed, no fumes, no strawberry cosplay. Just nature doing its shady, damp business. And very tasty business, too. "Great that you get on with real ecological preservation even if your taste in tree protection is questionable." And with the dignity of a former clan chief, he disappeared among the rocks, his antlers gleaming in the evening light. I remained by the Manners Stone a while longer, thinking about partnerships—including those with know-it-all but well-meaning deer. And I made a mental note to mark my calendar: third Thursday of every month, 3:00 to 4:00 pm. I had a feeling Magnus would have more advice to share.

A Load of Bull - Well, Deer Actually

I was in the middle of checking the tree guards around the young oaks when I spotted him—a glossy black beetle dragging something through the heather. It was hard to tell what exactly, but the three stubby horns on his head left no doubt: this was a minotaur beetle. And clearly on official duty. “Excuse me,” he called out without pausing in his efforts. “Would you mind giving me a quick hand? This batch turned out a little... larger than expected.” Third Thursday of the month, 3:20 pm. Of course. The Manners Stone had opened its monthly interspecies communication window. I crouched down beside him. “What are you hauling?” “Red deer dung. Top-quality stuff.” He gave the mass an encouraging push and beamed. “Dr Balthazar Beetlethorpe, if I may. Typhaeus typhoeus by species, dung collector by vocation.” “Pleasure to meet you. You seem quite... enthusiastic about your work.” “Oh, absolutely! It’s a highly underrated profession. Every dung type has its own personality. This one, for instance—” He patted the brown treasure affectionately. “—ideal moisture, beautiful density, rich nutritional profile. Magnus MacAntler is an excellent supplier. Very punctual. Real gentleman.” He resumed dragging, but kept talking. “Sheep dung, now—no disrespect to my colleagues—but it’s terribly bland. And there’s been this odd chemical aftertaste lately. I don’t get it. Things used to be different.” “How do you mean—different?” “Well, more... diverse back then. Nowadays it’s all very uniform. Bit dull, honestly.” He paused, scratched his head with a hind leg. “And don’t get me started on the sheep logistics. Someone told me they breed far more than they need here. Half of them get shipped off. By truck. To France!” “To France?” “Can you believe it?” He shook his head, baffled. “I can barely manage fifty metres to my nest, and they’re exporting livestock cross-continent.” He gave another tug on his fragrant cargo, then nodded towards my tree guards. “You’re planting trees, I see. Sensible. Although—” He gave the plastic tubes a disapproving glance. “—those things are right in the way when you’re trying to collect dung. Any chance you could use something... biodegradable? I’m particular about workplace ergonomics.” “I’ll see what I can do.” “Brilliant! You know, I’ve been collecting dung in this area for twelve years now. One develops standards. Red deer is premium—organic, free-range, ethically produced. My larvae get only the best.” He’d reached his burrow and began expertly rolling the load inside. “The secret is in proper storage,” he continued while manoeuvring the load into the tunnel. “Temperature, humidity, airflow—it all has to be just right. The larvae are very particular. And rightly so. You are what you eat, after all.” He vanished into the burrow for a moment, then popped back up, horns dusted with soil. “By the way—respectable work you’re doing up here. Trees increase biodiversity, and that means more dung variety. As a professional, I very much appreciate that.” He polished his three little horns with great ceremony. “If you ever need advice on sustainable dung management—happy to help. Many years of experience. Very client-focused.” And with a final satisfied glance at his well-stocked depot, Dr Balthazar Beetlethorpe disappeared into his subterranean realm. I sat there a while longer, thinking about quality standards, professional pride, and the wisdom of very small specialists who see the world from an entirely different angle.

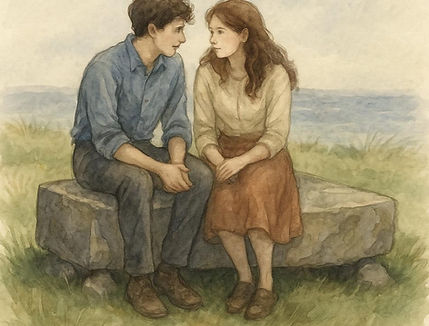

A Late Encounter

Back then they were sixteen. Secret meetings by the Manners Stone because their families simply had no words for each other beyond disapproval. A quiet understanding that one didn’t mix. So they met away from watchful eyes. The Manners Stone stood in the grass, wind-worn, grey, unremarkable. But it was theirs. There, they could talk, laugh, argue, kiss. They would place their hands on the stone and ask for things – sunshine, exam luck, endless summer. And one day, Claire told him: “If we ever lose each other, bring us back.” It felt like an incantation and James had nodded. They were happy. The kind of happy that stayed with you. Then her family moved away, suddenly, as these things happen. A letter or two, maybe, a rumour through someone else, then silence. Her life had been full with no regrets. And yet, sometimes, a thought would return – not quite longing, more like a tug in the memory. A place you step into in dreams without knowing why. There was a fracture in time, right where James had stood on their last afternoon with wind in his hair and a promise in his face. Now, exactly sixty years later, she was back on that hillside, not entirely sure what had brought her here. The path was harder, the air colder, her knees less forgiving. She had no idea why she had come all this way after such a long time, only that she had to. The stone was still there. Rough as ever – nothing seemed to have changed at all. Smaller though than she remembered it – but isn’t everything, once you have grown? And there was someone sitting on it. An old man, maybe a tourist resting? Slightly hunched, hands resting on his knees looking out to sea. She could have turned away, but something in his stillness, the way he held himself in the wind, made her pause. And when he turned his head, she knew. James. “I didn’t think you’d actually come,” he said. “Neither did I,” she replied. He smiled. And she understood that he had felt it too – not a call, not a sign, just that quiet certainty that it was time to return. They sat side by side., no need for catching up. Time didn’t run backwards. But it softened, like cloth folding. For a moment, they weren’t old, not young either. Just there. “Do you think it’s too late?” he asked. “No,” she said. “I think it’s now.” He gave a small laugh. “Looks like the stone remembered.” They sat a while longer until the cold told them it was evening. Then they went – carefully, but side by side. And the Manners Stone? It said nothing. But she could have sworn it nodded.